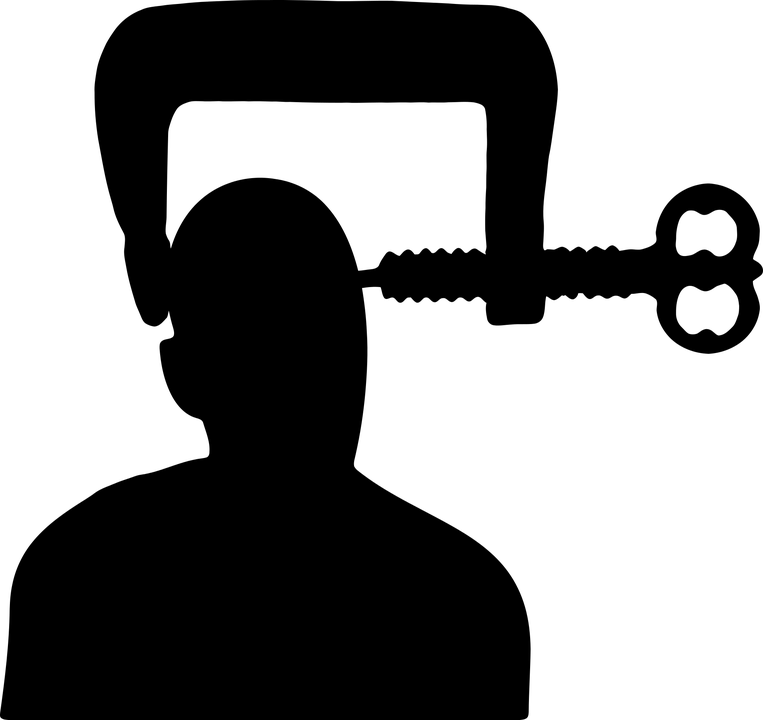

A system that is designed to eliminate fraud but has unwanted effects

These days the conditions for getting disability benefits and a blue badge are so extreme that many people who are genuinely in need and should be eligible are finding it difficult to qualify. There have also been many instances of the assessors deliberately lying or trying to catch out participants [2]. For me, hearing about this has definitely made me quite anxious about assessments, especially because I look fine. I can be totally exhausted and in extreme pain but I’m young and not naturally very expressive and you really can’t see it just by looking at me. You might see it if you know me and you’re looking with a sympathetic eye, but if you’re looking to fill quotas and save the government money, you could easily decide I look totally normal. Many people going through the process of applying for benefits are aware of the instances where assessors have disregarded what they have said instead commenting on how they looked and other superficial observations [1]. Unfortunately for many young people with severe degrees of conditions such as ME/CFS, MS, EDS, Fibromyalgia and so on, they feel a pressure to demonstrate their disability by walking in more agonised way, turning up at the assessment in pyjamas, using a stick etc. Something the majority of people don’t know is that pain is often delayed, so even if someone isn’t looking agonised now, they may feel it later. I’ve noticed that there has been some adjustment to the application forms to cater a bit more for fluctuating conditions and invisible illness but there’s still some way to go. It’s unfortunate that the very honest people who don’t exaggerate their condition at the assessment are possibly more likely to lose out than the (rare) people who are actually fine and made the whole thing up, and who are probably seasoned actors. Every time I have an assessment (and there seem to be many! Plenty of bureaucracy for the sick!) I do feel a pressure to look ill and in pain (which I often am), but at the same time I worry they’ll see me at another moment looking well and think I’m faking the whole thing! It’s a minefield!

A topic that’s hard to discuss

Another reason I feel like people think I’m faking it is because I rarely talk about how my condition affects me. It’s quite hard to fit into conversation sometimes, people rarely ask and it’s inevitably awkward, as you feel like you’re fishing for sympathy, and sometimes you get pity, or, alternatively, disbelief, which can be quite depressing/upsetting. But I know I need to discuss it more, because it’s just not something people know about, and I’m doing all these ‘odd’ things like sometimes using a stick/wheelchair and other times looking like I walk fine.

Mental ill-health

I think this is also an area that can really confuse people. I’ve found myself thinking ‘so-and-so is always laughing so he can’t be depressed’, and I’m sure that’s not the right way to look at it! I also knew a guy who stayed up all night before his assessment so he’d look ‘more obviously depressed’ by being dishevelled.

What can we do about the situation?

If you have a hidden disability:

- Try to talk about it more – it’s hard, but I know I need to do this

- Share this post with people, or similar posts

- Challenge any suspicions you may have about other people

If you don’t have one:

- Challenge your suspicions and try not to be as judgmental as we are encouraged to be

- If you find out someone you know has an invisible illness, say something like ‘I’m interested how the condition affects you, if you don’t mind sharing, so that way I can be more considerate about it’ – they’ll love you forever! And a lot more things will make sense. Do bear in mind they may only give you an edited version though, as actually detailing all the effects could take a long time for some people!

- Feel free to ask questions such as ‘how does it feel when you walk too much?’ – but make sure your tone is not suspicious or judgmental! Most people with invisible illnesses feel very judged already.

- Try not to expect people to look how they feel, and try not to assume it’s much worse to be physically unable to do something than to be able but only with significant negative effects.

- Try to read some or all of the blog posts in your feed about invisible conditions so you learn more.

What are your thoughts and experiences on this topic? Comment below!

If you found this post interesting, you might also like other posts on disability issues:

Feeling like a disability fake even when you’re not

Government finally reveals that more than 4000 died within six weeks of being deemed fit for work

Reflections on asking for help

Re-examining ‘fear of movement’ in chronic pain patients

Don’t focus on my impairment, ask me what I can bring to the role

We’ve got to stop pretending disability doesn’t exist

Chronic pain: an unrecognised taboo

References

[1] https://publications.parliament.uk/pa/cm201719/cmselect/cmworpen/355/35504.htm#_idTextAnchor019

[2] https://www.disabilitynewsservice.com/wow-questionnaire-responses-show-assessors-are-still-lying/ and https://www.disabilitynewsservice.com/pip-investigation-welfare-expert-says-two-thirds-of-appeals-involve-lying-assessors/ and https://publications.parliament.uk/pa/cm201719/cmselect/cmworpen/355/35504.htm and